Excerpt and illustrations from The Toilet, chapter 9 of The Young Lady’s Book by Abel Bowen, 1830.

Discourse we now of silks and cloth of gold;

Discourse we now of silks and cloth of gold;

Of robes for birth-days and high festivals;

The maiden’s simple, unadorn’d attire,

And of the modest toilet of the bride

OUR intention in the treatment of this delicate and important subject is by no means to attempt establishing a beau ideal of dress; because, even in the event of our being successful, it would be only applicable to the beau ideal of form and feature: indeed, it appears to us, that there is not only a perfect style of costume, adapted to the various classes of figure and face, but for almost every individual of which they are composed. To enter into a description of these styles, would be to embark into an hopeless and endless task; for, to be complete, they must be as infinite and varied as nature herself. Our limits may be much more advantageously occupied by an inquiry into general principles, leaving their application, in most cases, to the young reader’s taste, which, however, we shall endeavour in our progress, to correct, advance, or confirm.

Although the Toilet should never be suffered to engross so much of the attention as to interfere with the higher duties of life, yet, as a young lady’s dress, however simple, is considered a criterion of her taste, it is, certainly, worthy of her attention. Her chief object, in this respect, should be, to acquire sufficient skill and good taste to do all that is needful, with regard to the attire, in the least possible period of time, —to abbreviate the labours of the Toilet, so as not to entrench upon hours which should be devoted to the useful avocations of life, or the embellishments of the mind. It will be a laudable ambition in her, to curb those excesses of “each revolving mode” with which she is in some measure obliged to comply; to aim at grace and delicacy rather than richness of dress; to sacrifice exuberance of ornament (which is never becoming to the young) whenever it is possible, to an admirable neatness, equally distant from the prim and the negligent; to learn the valuable art of imparting a charm to the most simple article of dress, by its proper adjustment to the person, and by its harmonious blending, or agreeably contrasting with the other portions of the attire. It is a truth, which should ever be borne in mind, that a higher order of taste is often displayed, and a better effect produced, by a paucity or total absence of ornament, than by the most profuse and splendid decorations. The youthful Isabella of Portugal looks better in that simple head-dress in which she is occasionally depicted (Fig. 1) than in the nuptial robes which she wore on the day of her marriage with Philip the Good .

Although the Toilet should never be suffered to engross so much of the attention as to interfere with the higher duties of life, yet, as a young lady’s dress, however simple, is considered a criterion of her taste, it is, certainly, worthy of her attention. Her chief object, in this respect, should be, to acquire sufficient skill and good taste to do all that is needful, with regard to the attire, in the least possible period of time, —to abbreviate the labours of the Toilet, so as not to entrench upon hours which should be devoted to the useful avocations of life, or the embellishments of the mind. It will be a laudable ambition in her, to curb those excesses of “each revolving mode” with which she is in some measure obliged to comply; to aim at grace and delicacy rather than richness of dress; to sacrifice exuberance of ornament (which is never becoming to the young) whenever it is possible, to an admirable neatness, equally distant from the prim and the negligent; to learn the valuable art of imparting a charm to the most simple article of dress, by its proper adjustment to the person, and by its harmonious blending, or agreeably contrasting with the other portions of the attire. It is a truth, which should ever be borne in mind, that a higher order of taste is often displayed, and a better effect produced, by a paucity or total absence of ornament, than by the most profuse and splendid decorations. The youthful Isabella of Portugal looks better in that simple head-dress in which she is occasionally depicted (Fig. 1) than in the nuptial robes which she wore on the day of her marriage with Philip the Good .

There are many persons who, while they affect to despise Fashion, and are ostensibly the most bitter enemies of “the goddess with the rainbow zone,” are always making secret compacts and compositions with her.

Fashion demands a discreet, but not a servile observance: much judgment may be shown in the time, as well as the mode, chosen for complying with her caprices. It is injudicious to adopt every new style immediately it appears; for many novelties in dress prove unsuccessful, —being abandoned even before the first faint impression they produce is worn off; and a lady can scarcely look much more absurd than in a departed fashion, which, even during its brief existence, never attained a moderate share of popularity. The wearer must, therefore, at once relinquish the dress, or submit to the unpleasant result we have mentioned: so that, on the score of economy, as well as good taste, it is advisable not to be too eager in following the modes which whim or ingenuity create in such constant succession. On the other hand, it is unwise to linger so long as to suffer “Fashion’s ever-varying flower” to bud, blossom, and nearly “waste its sweetness” before we gather and wear it: many persons are guilty of this error; they cautiously abstain from a too early adoption of novelty, and fall into the opposite fault of becoming its proselytes at the eleventh hour: they actually disburse as much in dress as those who keep pace with the march of mode, and are always some months behind those who are about them; —affording, in autumn, a post-obit reminiscence to their acquaintance, of the fashions which were popular in the preceding spring.

Such persons labour under the further disadvantage of falling into each succeeding mode when time and circumstances have deformed and degraded it from its “high and palmy state:” they do not copy it in its original purity, but with all the deteriorating additions which are heaped upon it subsequently to its invention. However beautiful it may be, a fashion rarely exists in its pristine state of excellence long after it has become popular: its aberrations from the perfect are exaggerated at each remove; and if its form be in some measure preserved, it is displayed in unsuitable colours, or translated into inferior materials, until the original design becomes so vulgarized as to disgust.

There are many persons who, while they affect to despise Fashion, and are ostensibly the most bitter enemies of “the goddess with the rainbow zone,” are always making secret compacts and compositions with her. Their constant aim is to achieve the effect of every new style of dress, without betraying the most distant imitation of it: they pilfer the ideas of the modiste, which they use (to adopt the happy expression of Sir Fretful ) “as gipsies do stolen children, —disfigure them to make them pass for their own. ” This is pitiful hypocrisy.

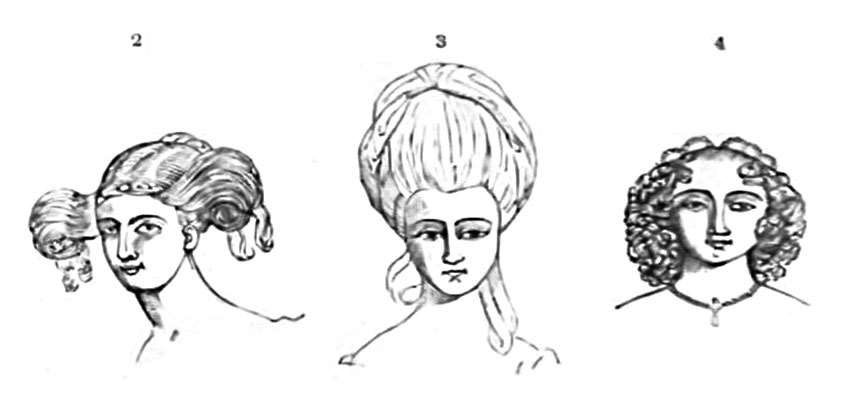

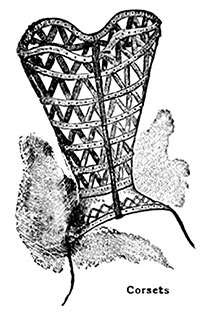

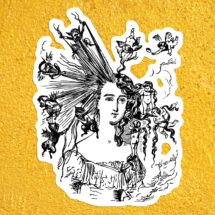

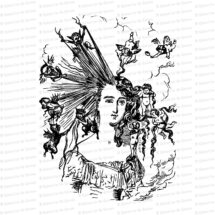

Although the fickle goddess rarely approaches the realms of the truly beautiful, except immediately after having rioted in the regions of absurdity; and scarcely sojourns in the classic air of Greece for a moment, ere she wings her way to that which is most Gothic and barbarous; yet, in spite of her absurdities, she is not only obeyed, but admired in all ages and in all climes. By the force of habit, and by an unconscious association in the mind of a dress and its wearer, Fashion, even to those who are somewhat fastidious, generally appears graceful. To please her, the fine lady of one country almost feeds herself into an apoplexy; and the would-be beauty of another, starves herself into “the sister to a shade”. The Chinese females cripple their feet; and the Europeans torture their waists into the narrowest possible compass. In one age she induces the fair sex to cover their faces with patches; and in the next, to blush if necessity compel them to apply one; alternately, to cashier, as it were, their natural tresses in favour of “false locks put on wires to make them stand at a distance from the head,” as the honest old herald, Randle Holme , describes the fashions of 1670 (Fig. 2;) —to elevate their hair to an immoderate height, as exhibited in the fine portraits of Sir Joshua Reynolds (Fig. 3;) —and to cultivate it into those ringlets drooping over the cars, so much admired in the fifteenth century, which have often come into partial favour during our own time (Fig. 4.)

Although the fickle goddess rarely approaches the realms of the truly beautiful, except immediately after having rioted in the regions of absurdity; and scarcely sojourns in the classic air of Greece for a moment, ere she wings her way to that which is most Gothic and barbarous; yet, in spite of her absurdities, she is not only obeyed, but admired in all ages and in all climes. By the force of habit, and by an unconscious association in the mind of a dress and its wearer, Fashion, even to those who are somewhat fastidious, generally appears graceful. To please her, the fine lady of one country almost feeds herself into an apoplexy; and the would-be beauty of another, starves herself into “the sister to a shade”. The Chinese females cripple their feet; and the Europeans torture their waists into the narrowest possible compass. In one age she induces the fair sex to cover their faces with patches; and in the next, to blush if necessity compel them to apply one; alternately, to cashier, as it were, their natural tresses in favour of “false locks put on wires to make them stand at a distance from the head,” as the honest old herald, Randle Holme , describes the fashions of 1670 (Fig. 2;) —to elevate their hair to an immoderate height, as exhibited in the fine portraits of Sir Joshua Reynolds (Fig. 3;) —and to cultivate it into those ringlets drooping over the cars, so much admired in the fifteenth century, which have often come into partial favour during our own time (Fig. 4.)

General fashions should certainly be conformed to, when, as Goldsmith observes, they happen not to be repugnant to private beauty. They may often be so modified as to suit the persons of all; and occasionally be so managed as to seem to have been created expressly for the most advantageous display of many individuals’ graces of form or delicacy of complexion. But alterations in modes must be made with considerable judgment, otherwise there is a risk of falling into absurdities : sometimes they are altogether intractable; it is impossible so to change a fashion, which has been especially invented for some tall and slender arbitress of taste, that it may at once retain much of its original character, and look becoming one whose form is either stout or petite. In this and similar cases the attempt should be abandoned, with the consoling idea, that the next mode will, in all probability, be decidedly advantageous to those who are, for the time being, debarred by nature from appearing at once graceful and fashionable, and the “Cynthias of the minute,” in their turn, be thrown into the shade; for the authenticity of every new edict of Fashion is usually warranted by the fact of its being directly opposite, in letter and spirit, to its predecessor: thus, if one year she elevate the zone to its utmost possible height, she generally depresses it in an equally unreasonable degree the next; if she prescribe evergreens for the embellishment of the hair, in June , she commands “summer’s glowing coronal,” for the same purpose, in December. Should high flounces be patronized, short ladies must abstain from adopting them, because they are becoming only to the tall; and if narrow dresses obtain pre-eminence, the slender must not sacrifice that fulness in the attire, for which, to them, the most exquisite display of fashion can never be a sufficient compensation. The example of those who have long necks and low shoulders, should never lead those of a different style of person, to wear necklaces of great breadth, to raise the dress towards the ears, or, by quantity of drapery, or profusion of ornament, to produce an apparent union of the head-gear and the shoulders. Such a costume as that of Elizabeth of York , queen of Henry the Seventh (Fig . 5,) may add dignity to a certain order of forms, but it would certainly produce a contrary effect on the appearance of those who have neither long necks nor depressed shoulders.

General fashions should certainly be conformed to, when, as Goldsmith observes, they happen not to be repugnant to private beauty. They may often be so modified as to suit the persons of all; and occasionally be so managed as to seem to have been created expressly for the most advantageous display of many individuals’ graces of form or delicacy of complexion. But alterations in modes must be made with considerable judgment, otherwise there is a risk of falling into absurdities : sometimes they are altogether intractable; it is impossible so to change a fashion, which has been especially invented for some tall and slender arbitress of taste, that it may at once retain much of its original character, and look becoming one whose form is either stout or petite. In this and similar cases the attempt should be abandoned, with the consoling idea, that the next mode will, in all probability, be decidedly advantageous to those who are, for the time being, debarred by nature from appearing at once graceful and fashionable, and the “Cynthias of the minute,” in their turn, be thrown into the shade; for the authenticity of every new edict of Fashion is usually warranted by the fact of its being directly opposite, in letter and spirit, to its predecessor: thus, if one year she elevate the zone to its utmost possible height, she generally depresses it in an equally unreasonable degree the next; if she prescribe evergreens for the embellishment of the hair, in June , she commands “summer’s glowing coronal,” for the same purpose, in December. Should high flounces be patronized, short ladies must abstain from adopting them, because they are becoming only to the tall; and if narrow dresses obtain pre-eminence, the slender must not sacrifice that fulness in the attire, for which, to them, the most exquisite display of fashion can never be a sufficient compensation. The example of those who have long necks and low shoulders, should never lead those of a different style of person, to wear necklaces of great breadth, to raise the dress towards the ears, or, by quantity of drapery, or profusion of ornament, to produce an apparent union of the head-gear and the shoulders. Such a costume as that of Elizabeth of York , queen of Henry the Seventh (Fig . 5,) may add dignity to a certain order of forms, but it would certainly produce a contrary effect on the appearance of those who have neither long necks nor depressed shoulders.

Jewellery should never be used to cover any imperfections of form in the neck; it is in much better taste, for such a purpose, to wear a neat collar, reaching as high as the cheek ( Fig. 6, Mary Queen of England .) Those who happen to be faultless in this respect, look better, perhaps, with the neck altogether unadorned (Figs. 7 and 8, costumes of Mary de Berri , wife of John Duke of Bourbon , and of Anne Boleyn .)

Jewellery should never be used to cover any imperfections of form in the neck; it is in much better taste, for such a purpose, to wear a neat collar, reaching as high as the cheek ( Fig. 6, Mary Queen of England .) Those who happen to be faultless in this respect, look better, perhaps, with the neck altogether unadorned (Figs. 7 and 8, costumes of Mary de Berri , wife of John Duke of Bourbon , and of Anne Boleyn .)

Whatever be the reigning mode, and however beautiful a fine head of hair may be generally esteemed, those who are short in stature, or small in features, should never indulge in a profuse display of their tresses, if they would, in the one case, avoid the appearance of dwarfishness and unnatural size of the head, and in the other, of making the face seem less than it actually is, and thus causing what is merely petite to appear insignificant. If the hair be closely dressed by others, those who have round or broad faces should, nevertheless, continue to wear drooping clusters of curls; and, although it be customary to part the hair in the centre, the division should be made on one side, if it grow low on the forehead and beautifully high on the temples; but if the hair be too distant from the eyebrows, it should be parted only in the middle, where it is generally lower than at the sides, whatever temptations Fashion may offer to the contrary .

We might multiply instances ad libitum; but the foregoing cases will, we doubt not, satisfactorily elucidate our proposition. It is our object to impress on our readers, the propriety of complying with the ordinances of Fashion, when their observance is not forbidden, by individual peculiarities; and the necessity of fearlessly setting them at defiance, or offering only a partial obedience, when a compliance with them would be positively detrimental to personal grace: by those means they may escape the imputation of resembling those pictures, in which “the face is the work of a Raphael , but the draperies are thrown out by some empty pretender, destitute of taste, and entirely unacquainted with design.”

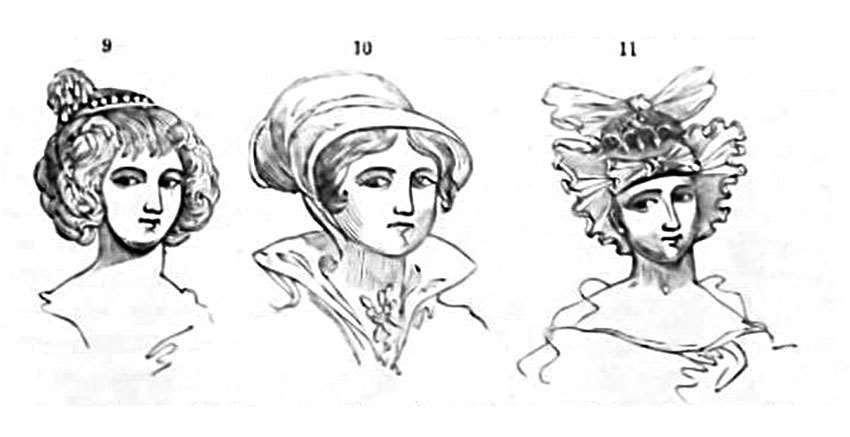

To form the taste and improve the style of dress, a careful observation of classical figures, and some of the costumes of by-gone centuries, will, doubtless, be found of considerable advantage. Let not the reader imagine that it is impossible to borrow hints for the attire from such sources without incurring a risk of appearing somewhat antiquated; for several of the most popular modes of the present century have been mere revivals of ancient costumes. Prince Rupert’s mother appears to have dressed her hair very much in the same manner as a number of ladies did only a few years since (Fig. 9;) and the gentle Lady Jane Grey’s attire (Fig. 10) is very similar to that of a plainly-dressed young woman of our own time; but these are minor resemblances to what some of the costumes of past times afford. The female head-dress in 1688 (Fig. 11,) instance, is remarkably similar to that which was very lately in fashion among the ladies of this country. Holme states, that the forehead was adorned with a knot of divers-coloured ribbons, the head with a ruffle quoif set in corners, and the like ribbons behind the head: and this mode does not appear to have been an invention of our author’s day, but rather a revival of some mode of a still more remote period; for, in speaking of this and other devices of the like nature, he says, all are brought again from the old; for there is no new thing under the sun, and what is now hath been formerly.

To form the taste and improve the style of dress, a careful observation of classical figures, and some of the costumes of by-gone centuries, will, doubtless, be found of considerable advantage. Let not the reader imagine that it is impossible to borrow hints for the attire from such sources without incurring a risk of appearing somewhat antiquated; for several of the most popular modes of the present century have been mere revivals of ancient costumes. Prince Rupert’s mother appears to have dressed her hair very much in the same manner as a number of ladies did only a few years since (Fig. 9;) and the gentle Lady Jane Grey’s attire (Fig. 10) is very similar to that of a plainly-dressed young woman of our own time; but these are minor resemblances to what some of the costumes of past times afford. The female head-dress in 1688 (Fig. 11,) instance, is remarkably similar to that which was very lately in fashion among the ladies of this country. Holme states, that the forehead was adorned with a knot of divers-coloured ribbons, the head with a ruffle quoif set in corners, and the like ribbons behind the head: and this mode does not appear to have been an invention of our author’s day, but rather a revival of some mode of a still more remote period; for, in speaking of this and other devices of the like nature, he says, all are brought again from the old; for there is no new thing under the sun, and what is now hath been formerly.

We have still a much more singular coincidence of coeffure in reserve than any that have hidierto been noticed. However strange the statement may appear in words, it is true in fact, that the small bonnets worn by the ladies of England a few years ago, and which struck our neighbours, the French, as being so excessively ridiculous, that they are still found in their caricatures of English women, —those awkward, inelegant, and now deservedly-abolished little bonnets, —are almost facsimiles of the helmet of Minerva, on Lord Montague’s chrysolite (Fig. 12.)

We have still a much more singular coincidence of coeffure in reserve than any that have hidierto been noticed. However strange the statement may appear in words, it is true in fact, that the small bonnets worn by the ladies of England a few years ago, and which struck our neighbours, the French, as being so excessively ridiculous, that they are still found in their caricatures of English women, —those awkward, inelegant, and now deservedly-abolished little bonnets, —are almost facsimiles of the helmet of Minerva, on Lord Montague’s chrysolite (Fig. 12.)

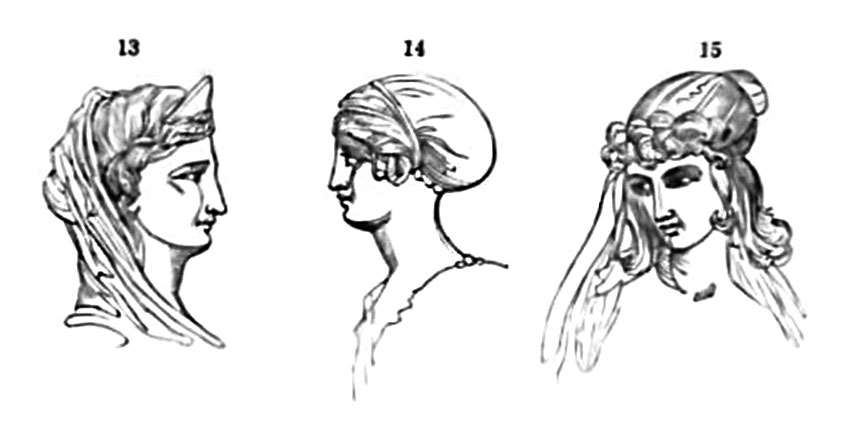

In attempting to engraft any part of the attire of olden times upon modern styles, as much discretion and judgment are required as in the modification of an ephemeral fashion to personal peculiarities: in the words of an Eastern sage, it is not enough that we go into the valley of flowers to gather a rose, —even there we should not snatch, but select. In turning over the leaves of a portfolio of old prints, or a richly-illuminated missal, a lady must not hastily adopt a head-dress because it is attractive and unexceptionable in the place it occupies: —she should rather consider, in the first place, whether it will admit of being incorporated with the style of the day; and next, if it will become her own figure or features. The coeffure of Sappho, however classical it may be, would by no means suit a round and (if we may use the term) rural face; the Greek style of head-dress requires features of a Grecian form; and there are few faces that can afford to cover the finer portion of the forehead by natural curls, or artificial ornament. ( Fig . 13, head of Sappho . Fig . 14, Greek head, from a gem. Fig . 15, the Taure head-dress of 1674.)

In attempting to engraft any part of the attire of olden times upon modern styles, as much discretion and judgment are required as in the modification of an ephemeral fashion to personal peculiarities: in the words of an Eastern sage, it is not enough that we go into the valley of flowers to gather a rose, —even there we should not snatch, but select. In turning over the leaves of a portfolio of old prints, or a richly-illuminated missal, a lady must not hastily adopt a head-dress because it is attractive and unexceptionable in the place it occupies: —she should rather consider, in the first place, whether it will admit of being incorporated with the style of the day; and next, if it will become her own figure or features. The coeffure of Sappho, however classical it may be, would by no means suit a round and (if we may use the term) rural face; the Greek style of head-dress requires features of a Grecian form; and there are few faces that can afford to cover the finer portion of the forehead by natural curls, or artificial ornament. ( Fig . 13, head of Sappho . Fig . 14, Greek head, from a gem. Fig . 15, the Taure head-dress of 1674.)

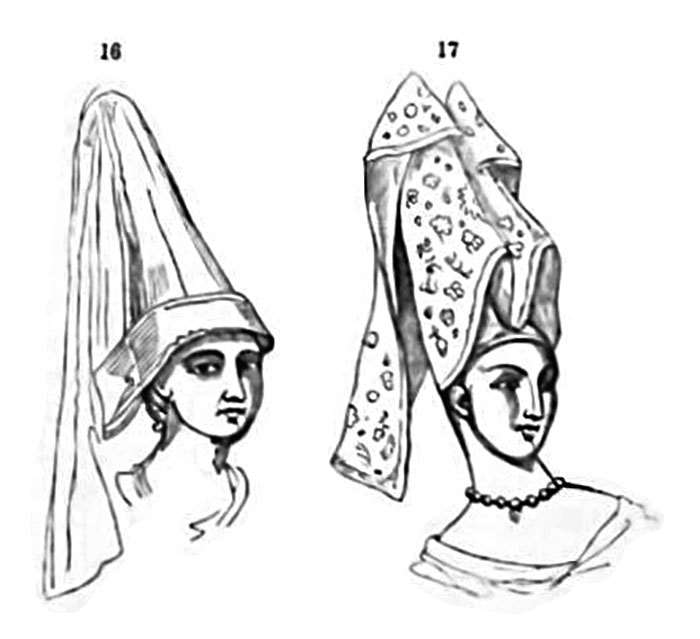

Although sharp features will never he improved by their being surmounted with a cone-shaped cap; nor a short face, or one which expresses a meek and retiring disposition, by a regal coeffure, there are classes of features to which either of these styles would be suitable. (Fig. 16, head of the Dauphiness Margaret of Scotland , 1400. Fig. 17, Train-bearer to Isabella, of Bavaria, Queen of Charles the Sixth of France.)

Although sharp features will never he improved by their being surmounted with a cone-shaped cap; nor a short face, or one which expresses a meek and retiring disposition, by a regal coeffure, there are classes of features to which either of these styles would be suitable. (Fig. 16, head of the Dauphiness Margaret of Scotland , 1400. Fig. 17, Train-bearer to Isabella, of Bavaria, Queen of Charles the Sixth of France.)

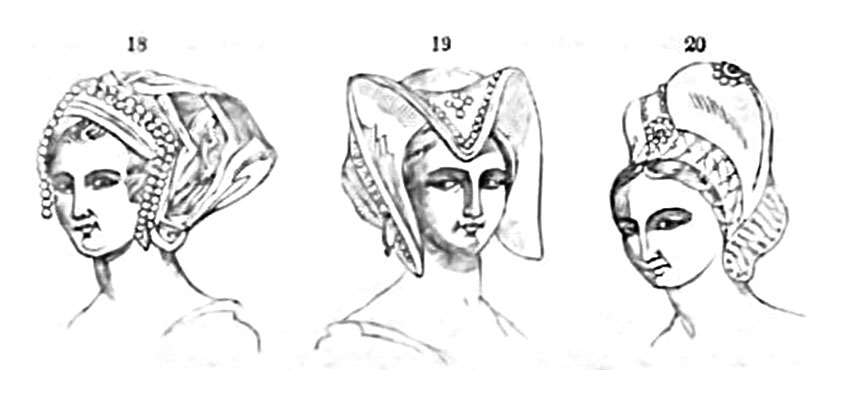

But even those to whom such costumes would be very becoming, must not venture to adopt them when low head-dresses are exclusively worn. They must then rather have recourse to the pictorial records of those eras when comparatively low coeffures were in vogue (Figs. 18, 19, and 20, head-dresses in Luther’s time.)

It is almost impossible to form a theory of the proper combination of colours applicable to dress: they are subject to a thousand contingencies, and we daily discover agreeable harmonics of tint where we least expected them, and excruciating discords produced by the juxtaposition of hues, which, from our previous experience, we were induced to imagine would prove pleasing rather than offensive. The influence of some neighbouring tint, the position of the colours combined, their relative stations, and the materials adopted for each, frequently tend to produce these effects. The colour of a single rosette often destroys the general tone and appearance of the dress, and occasionally it may be managed with such skill as to blend the tints of two or more principal parts of the costume, which, without some such mediator, would render each other obnoxious to the eye of taste. It is quite certain, that the same colour, which imparts a liveliness and brilliancy when used for light embellishments, and in a small quantity, becomes vulgar, showy, and disagreeable, if adopted for the most extensive portion and leading tint of the attire; and, on the other hand, the delicate or neutral colours, which look well when displayed over a considerable surface, dwindle into insignificance if used in small detached portions for minor ornaments.

It is almost impossible to form a theory of the proper combination of colours applicable to dress: they are subject to a thousand contingencies, and we daily discover agreeable harmonics of tint where we least expected them, and excruciating discords produced by the juxtaposition of hues, which, from our previous experience, we were induced to imagine would prove pleasing rather than offensive. The influence of some neighbouring tint, the position of the colours combined, their relative stations, and the materials adopted for each, frequently tend to produce these effects. The colour of a single rosette often destroys the general tone and appearance of the dress, and occasionally it may be managed with such skill as to blend the tints of two or more principal parts of the costume, which, without some such mediator, would render each other obnoxious to the eye of taste. It is quite certain, that the same colour, which imparts a liveliness and brilliancy when used for light embellishments, and in a small quantity, becomes vulgar, showy, and disagreeable, if adopted for the most extensive portion and leading tint of the attire; and, on the other hand, the delicate or neutral colours, which look well when displayed over a considerable surface, dwindle into insignificance if used in small detached portions for minor ornaments.

Generally speaking , trimmings will bear a greater richness of colours than the principal material of the dress, the breadth of which is apt entirely to subdue its decorations if they be not a little more powerful in tint. But it is a grave error to endow the minor parts of the costume with an undue superiority our the rest; it should never be forgotten, that the trimming is intended to embellish the dress, rather than that the dress should sink into a mere field for the display of the trimming, sufficient importance should always be given to the latter, so that it may enhance the beauty, add to the richness, or harmonize with the purity and neatness of the former; but if its colours be too strong, or even when of the proper shade, if the material be too profuse, or not of a quality sufficiently delicate, it gives to the wearer either a frittered, gaudy, or coarse appearance, according to the nature of the fault. The same tint which looks well in a delicate material, will not become an article which is made of “sterner stuff.”

Coloured shoes, we need scarcely say, are exceedingly vulgar…

The occurrence of glaring offences against good taste in the trimmings or fixed embellishments of any principal part of the attire, is rare, compared with those which are perpetrated in the minor articles of gloves, shoes, ribbons, &c. which are the more important of the two, because they are not the trimmings or finishing decorations of a part, but to the whole of the costume. The former are usually left to the experience of the milliner, or copied from the production of some tasteful modiste; the latter depend solely on the judgment of the private individual. How often have we seen a dress, exquisite in all its parts, utterly ruined, by the wearer, as a finishing touch, drawing on a vulgar glove! Much mischief of a similar nature is frequently done, by feathers, flowers, ribbons, shoes, and articles of jewellery. It is not enough that a flower is pretty; it must harmonize with, or form a pleasing contrast to the other parts of the costume, otherwise its use must be rigorously forbidden. It is the same with jewellery: pearls, for instance, will suit those kinds of dresses which rubies would spoil; and the latter are appropriate in cases where the former would look faint and ineffective. Coloured shoes, we need scarcely say, are exceedingly vulgar: delicate pink, and faint-blue silk, for these articles, have numerous advocates; but white satin, black satin or kid, and bronze kid, are neater and more elegant than any other colour or material. Gloves should be in the most delicate tints that can be procured: their colour has always an effect upon the general appearance; one kind of hue must not, therefore, be indiscriminately worn, or, however beautiful it may be in itself, obstinately persisted in, when every other part of the attire is constantly subject to change.

As it would be in bad taste for a fair young lady, who is rather short in stature, however pretty she may be, if irregular as well as petite in her features, to take for a model, in the arrangement of her hair, a cast from a Greek head; so also would it for one, whose features are large, to fritter away her hair, —which ought to be kept, as much as possible, in masses of large curls, so as to subdue, or, at least, harmonize with her features, —into such thin and meagre ringlets as we have seen, trickling, “few and far between,” down the white brow of a portrait done in the days of our first King Charles. Yet there is a class of features, to which even these are becoming: of this we may be convinced by a glance at a collection of portraits of that period; unless, indeed, it be true, that fine features, when ennobled by the inward light of intelligence, purity, and goodness, look well in any fashion; —that they govern and give character to the style in which they are dressed, and impart a charm to, rather than receive any benefit from, either modes or ornaments. Even if this be the case, there are but few heads which possess, in a sufficient degree, the power to defy the imputation of looking absurd, or inelegant, if the hair be dressed in a style inconsistent with the character of the face, according to those canons of criticism which are founded upon the principles of a pure and correct taste, and established by the opinions of the most renowned painters and sculptors, in every highly-civilized nation, for ages past.

In the arrangement of the hair, according to the shape of the face, and expression of the features, —in the harmonizing of the colours, used in dress, with the tint of the complexion, —in the adaptation of form, fashion, and even material, to the person, —there is an ideal beauty, as well as in the figure itself: this beauty is well understood; but it is very difficult, —nay, almost impossible, —to describe; for it must be considered in relation to, and as modified by, the infinite varieties of form, feature, and complexion. The shades of difference are often so minute; —the intermixtures of various styles of person (if we may use the expression) are so manifold; —Nature is so illimitable in her beautiful combinations; —that, although we may legislate for the few, —the very few, who are of any decided order of form, feature, or complexion, —we cannot do so for the greater portion, —the numberless individuals who, though by no means less attractive, may be said to belong to no class, but unite the peculiarities of many.

It is admitted, that the brunette will look best in one colour, and the blonde in another; —that to the oval face a particular style of dressing the hair is most becoming; and to the elongated, a mode directly the reverse; —that the short should not wear their dresses flounced so high as the tall: —but in saying this, we are speaking to a comparatively small number of persons. The decidedly dark, and those of a positively opposite complexion, are few: it is the same with the tall and the short, —those with round faces, and the contrary: in each case, the multitude is to be found “in the golden mean,” between the two extremes. The persons composing the majority should neither adopt the specific uniform of the blonde or the brunette, —the style of dress suitable to the lofty and commanding figure, or to that of the pretty and petite; but modify general principles to particular cases; —not by producing an heterogeneous mixture of a number of different styles, but by adopting a mode which borders upon that adapted to the class to which their persons approach the nearest, without entirely losing sight of, and in some degree being governed by, their own distinguishing and specific peculiarities: —in fact, to be guided by that indispensable and ruling power in all matters connected with the Toilet, —taste; which, as Demosthenes said of action in relation to eloquence, is the first, second, and third grand requisite, combining the triple qualities of propriety, neatness, and elegance. By its powerful aid, the most simple materials are rendered valuable; without it, the richest robes, the most costly jewels, and “tresses like the morn,” may be so employed as to encumber rather than to adorn.

It is admitted, that the brunette will look best in one colour, and the blonde in another; —that to the oval face a particular style of dressing the hair is most becoming; and to the elongated, a mode directly the reverse; —that the short should not wear their dresses flounced so high as the tall: —but in saying this, we are speaking to a comparatively small number of persons. The decidedly dark, and those of a positively opposite complexion, are few: it is the same with the tall and the short, —those with round faces, and the contrary: in each case, the multitude is to be found “in the golden mean,” between the two extremes. The persons composing the majority should neither adopt the specific uniform of the blonde or the brunette, —the style of dress suitable to the lofty and commanding figure, or to that of the pretty and petite; but modify general principles to particular cases; —not by producing an heterogeneous mixture of a number of different styles, but by adopting a mode which borders upon that adapted to the class to which their persons approach the nearest, without entirely losing sight of, and in some degree being governed by, their own distinguishing and specific peculiarities: —in fact, to be guided by that indispensable and ruling power in all matters connected with the Toilet, —taste; which, as Demosthenes said of action in relation to eloquence, is the first, second, and third grand requisite, combining the triple qualities of propriety, neatness, and elegance. By its powerful aid, the most simple materials are rendered valuable; without it, the richest robes, the most costly jewels, and “tresses like the morn,” may be so employed as to encumber rather than to adorn.

You must be logged in to post a comment.