Inscription

W.L. Lloyd

References

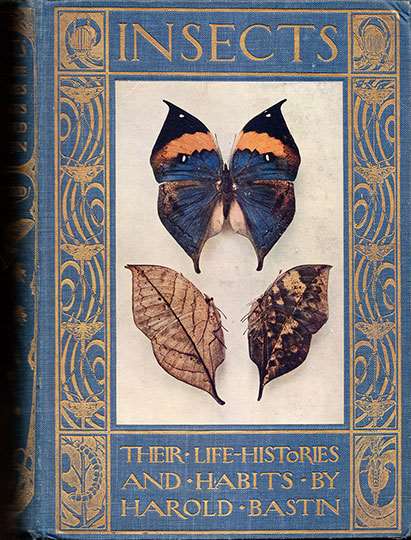

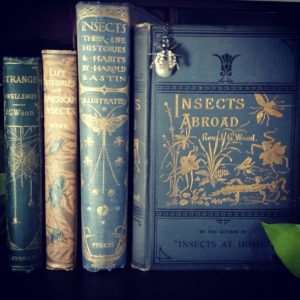

“INSECTS, THEIR LIFE HISTORIES AND HABITS. By H. Bastin. London: T.C. and E.C. Jack. Pp. xii. 349 and 46 plates. 7s. 6d. net.

Mr. Bastin’s book is more than an account of the habits and life-histories of insects; it is a plainly written and very interesting study of those adaptations of structure and behaviour that have made the insects one of the dominant groups of animals. Dominance means abundance of individuals, persistence throughout geological time, and the ability to live and reproduce amid the most varied physical conditions; and it has been attained among the arthropods, as among the vertebrates, by a plasticity of structure and behaviour which has enabled these animals to fit themselves for the almost every kind of environment possible upon the earth. With this idea continually in his mind, Mr. Bastin describes the structure and classification of insects; their sensations and behaviour; their life-histories; their modes of reproduction; their societies; their means of defence and aggression: in short, all the factors which have made insects the most dominant group of animals at present existing on the earth.

He is least successful in his treatment of the problem of instinct and intelligence among these animals. Instincts, for him, are inevitable modes of behaviour arising in the course of evolution from ‘tropisms’ – that is, such purely physical responses to eternal stimuli as are illustrated b the turning of the green leaf towards a source of light. Followed to its logical conclusion, this conception of the behaviour of the lower animals forces us to regard their activities as automatic and unconscious. Now the more we think about it the more probable does Bergson’s interpretation fo the evolutionary process seem to be. Life has evolved along three directions: (1) the chlorophyllian organisms resulting in the great trees and grasses – these are the dominant plants; (2) the arthropods, represented most typically by the hymenopterous insects; and (3) the vertebrates, culminating in man. The evolution has not only been that of structure and function, but it has been a physical evolution. Unconsciousness and immobility characterise the typical plant, and mobility and consciousness the animal. But this ‘consciousness’ of the animal has split, and is manifested in the insect by instinct, which is yet tinged by what remains of the original physical tendency; that is, it is tinged by intelligence. The actions of the vertebrate are in the main intelligent, but round them cling the remnants of instinct. Intelligence and instinct are therefore divergent lines of evolution resulting from the cleavage of an original single tendency. Between intelligence and rationality, says Mr. Bastin, there is a great gulf, and this has never been crossed by insects. Yet, we think, minute analysis of the actions of his insects might convince him that the gulf is not impassable.”

– The Guardian, London, England, 28 May 1913

You must be logged in to post a comment.